George Whitman is dead at the age of 98 and my Paris friends are all planning to join a cortege to his Père Lachaise funeral next week. I cannot join them, sadly, since I am imprisoned in Chicago by client obligations and financial circumstances and can’t return to visit Paris until January.

There are many of us for whom George has always been an integral part of Paris – and for whom his death is a tragedy of indescribable proportions, notwithstanding his age and recent stroke and the obvious inevitability.

George arrived in Paris in 1948. In 1951 he opened the now iconic Shakespeare and Company English language bookstore at 37, rue de la Bucherie – at first named Le Mistral, but later renamed after the famous bookstore that his friend Sylvia Beach had once run on rue de l’Odeon.

Sylvia mentored and supported the likes of Ernest Hemingway and James Joyce and even published Ulysses when no one else would touch what the world then considered a scandalous book. Like Sylvia, George has always given succor and literary encouragement to writers. He even offered young and impoverished authors a home in the store. He let them sleep on benches and behind bookshelves in exchange for duties such as book shelving, cash-register manning, and dish washing – and in exchange for following his rules, which included writing their biographies on a small portable typewriter for his archives, and reading one book a day.

He called them “tumbleweeds” and liked to quote Yeats, who wrote: “Be not inhospitable to strangers, lest they be angels in disguise.”

I, too, was once a momentary “tumbleweed,” though I am a middle-age lawyer, only a sometime writer, and not impoverished. Nevertheless, writing is my passion, and I like to dream that I live in Paris and write full time.

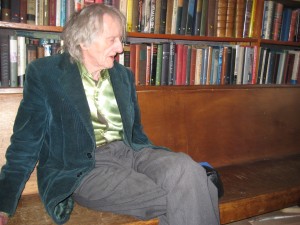

As part of that dream, I walked into Shakespeare & Company one day and, on a whim, asked George if even people my age could stay there. He asked if I was a writer and I demurred and admitted that I was not published. He again asked: “Do you write?” Of course I said I did – and spent a night with the current contingent of young and penniless writers in residence there. George actually found a small bed for me (because of my age, I guess) and I was not put to work in the store – but I did have to tap out my biography on that little typewriter and provide a picture for his archives.

My fellow residents taught me how to pitch a small stone at a window to be let into the door after George’s midnight curfew, and I woke the next morning to the hope of a writer’s life and the view of a beautiful new day lighting the turrets of Notre Dame just across a sliver of the River Seine.

I have returned numerous times – not to sleep there, but to see George, to get to know his daughter Sylvia – who returned to him in recent years after growing up in England with her mother (and whose full name is Sylvia Beach Whitman, after guess who?), to attend the Sunday afternoon “tea parties” where locals, tourists, and even the famous gather to eat cookies, share stories, and sip tea served by “tumbleweeds.” One Sunday, I found myself sitting next to George’s good friend, famous San Francisco beat poet Laurence Ferlinghetti.

Sometimes, I attend the Monday-night book readings, and sometimes just wander the narrow aisles, pick up a book or two, or sit upstairs in the public “library” to read or write.

Sometimes George didn’t recognize me, and sometimes he said, “Oh, there’s the Chicago lawyer.” Sometimes George was cordial, and sometimes…not so much.

I once tried to purchase a book about Gertrude Stein that George apparently thought should have remained upstairs in the “library” – where books are for customers to read, but are not for sale. It had somehow made its way onto the main floor shelves, and there I was trying to pay for it at the register. “You can’t buy that” he shouted at me as he tossed the book across the counter. He calmed down when I begged him to let me keep it for just a few days with a promise to return it. We made the deal.

I was standing late one night at the reception area of Hotel Marignan on rue de Sommerard when George walked in to ask if they had a cheap room available. He carried an old torn gym bag, and his hair was flying (probably from his latest “haircut” – with the flame of a candle), and for a moment (until he was recognized) the receptionist recoiled and tried to turn him away. George had, that night, given up his own bed above the store to a writer who had arrived unexpectedly.

It was at Shakespeare and Company, in the second floor “library,” where I first met my now great friend, author, and Paris historian Thirza Vallois – whose Paris books are not just walking tours but a wealth of historic information.

It was at Shakespeare and Company where I met my friend Jonathon, a young man from Ireland who writes pithy and quirky prose and who worked there for years. Many an evening, I sat near the cash register on a small bench against the shelves and talked literature, Paris, and just stuff with Jonathon. He left Shakespeare a few years ago to get a college education in London, and is now a rare bookseller in Paris.

The day after George’s death, Jonathan e-mailed me that he and 30 others had stood in the cold outside the store to watch as George was carried out, and that as he wrote his e-mail to me he was listening to My Way and tears were running down his face.

I understood the emotion.

I will miss George. We all will.

Editor’s note: In 2006 George Whitman was awarded the Officier des Arts et Lettres by the French Minister of Culture for his lifelong contribution to the arts.

Like our blog? Join us on Facebook!