As I am on the mailing list of ExploreParis, a collaborative project of diverse organizations involved in the tourist industry in the greater Parisian area, I recently received a notice that a small coffee roasting facility in the nearby town of Montreuil was holding an open house to demonstrate coffee roasting followed by a tasting. I purchased a ticket online and made my way to Capuch’ on a recent Saturday morning.

Getting there was not difficult because Paris and the surrounding region have a wonderfully integrated mass transit system.

Capuch’ proprietor Julie Caron gave a tour of her facility to a small group of coffee enthusiasts, of which I was one. She is pictured here holding a Chemex coffee beaker, which she used to make coffee after she demonstrated the roasting process.

Julie was enthusiastic about her gas-fired, Turkish-model coffee roasting machine. Not pictured is the complex system of extracting and filtering the fumes produced by the roasting process before they are evacuated out of the shop. In the neighborhood in which I live in Paris I have sometimes noticed the wonderful aroma of freshly-roasted coffee wafting out of one of the local coffee-roasting facilities as I walk to the metro. I never realized, until I saw Julie’s demonstration, how much care had to be taken to keep the chaff of the roasted beans from floating onto the street.

Julie had purchased a 69kg bag of unroasted coffee beans from Guatemala.

She then removed a small batch of the beans from the bag, weighed it, and sifted through the beans to remove debris and small pebbles.

Prior to examining them, she turned on the roaster to heat it up.

Once the roaster was hot, and after carefully scrutinizing the small batch of beans, she poured 3.5 kg of them into the hopper of the coffee roaster. (The capacity of the roaster is 5kg.)

The drum of the roaster turns in the gas-fired chamber, roasting the beans slowly.

Julie explained that the roasting process is monitored three ways: visually, aurally, and olfactorily. In the photo above, she is is listening for the “crack” (like popcorn) of the coffee beans, which is a sign of their doneness. She is also pulling out the sampling spoon, which is used to check the scent of the roast. To the right of the spoon, you can see a small round observation window that permits the operator to view the progressive darkening of the beans during the roasting process.

Julie gave each participant a chance to experience the maturing aroma of the beans during the roasting process.

Finally, the roasting process was finished and Julie opened the drum to transfer the beans to the cooling tray. Once cooled, she would transfer them to a canister where they would remain for 24 hours while they released CO₂.

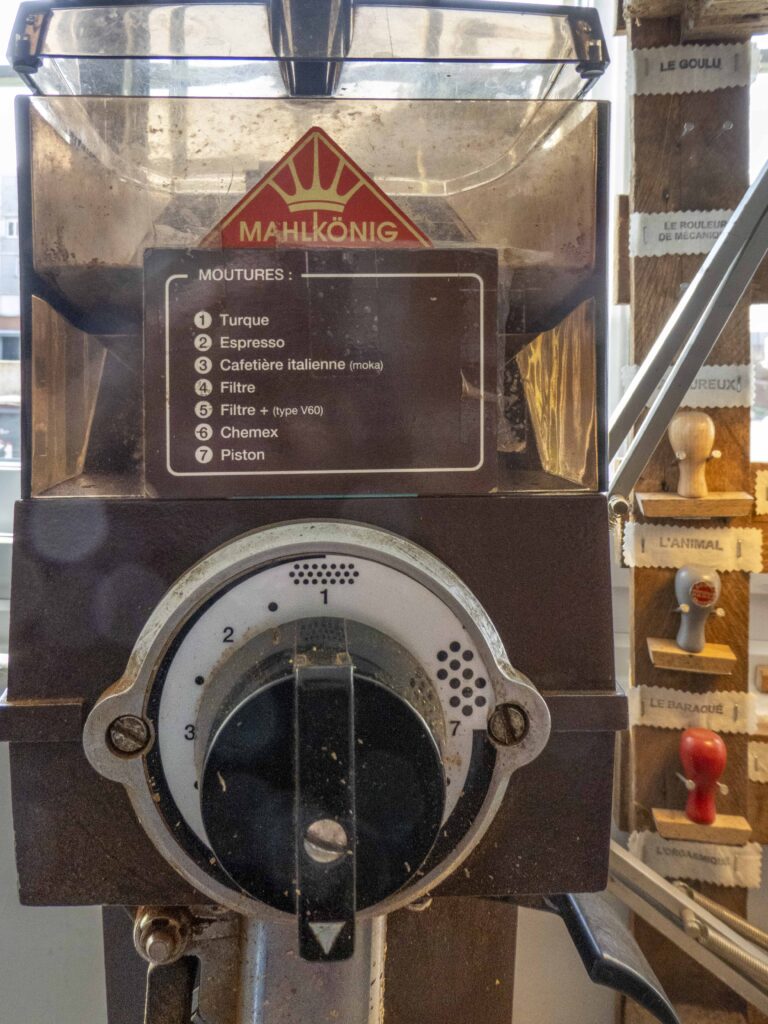

After the coffee-roasting demonstration, Julie took a small batch of beans that she had roasted the day before and ground them to prepare them for the pour-over coffee-making demonstration.

She demonstrated the pour-over technique of preparing coffee using a Chemex beaker.

This technique produced four cups of coffee, one for each of the participants.

I purchased a 250g bag of Guatemala Huehuetenango “Le Rêveur” from the batch that Julie had roasted the day before my visit. The tasting notes on the bag indicated that I would experience aromas of chocolate and cooked fruit.

Back home, I ground 18g of the beans finely and used my 9Barista stove-top espresso machine to produce a robust coffee that did, indeed, express aromas of chocolate and cherry. Because it was prepared as espresso, it was stronger than what I experienced at the roasting facility.

Capuch’

8, rue Eugène Varlin

93100 Montreuil